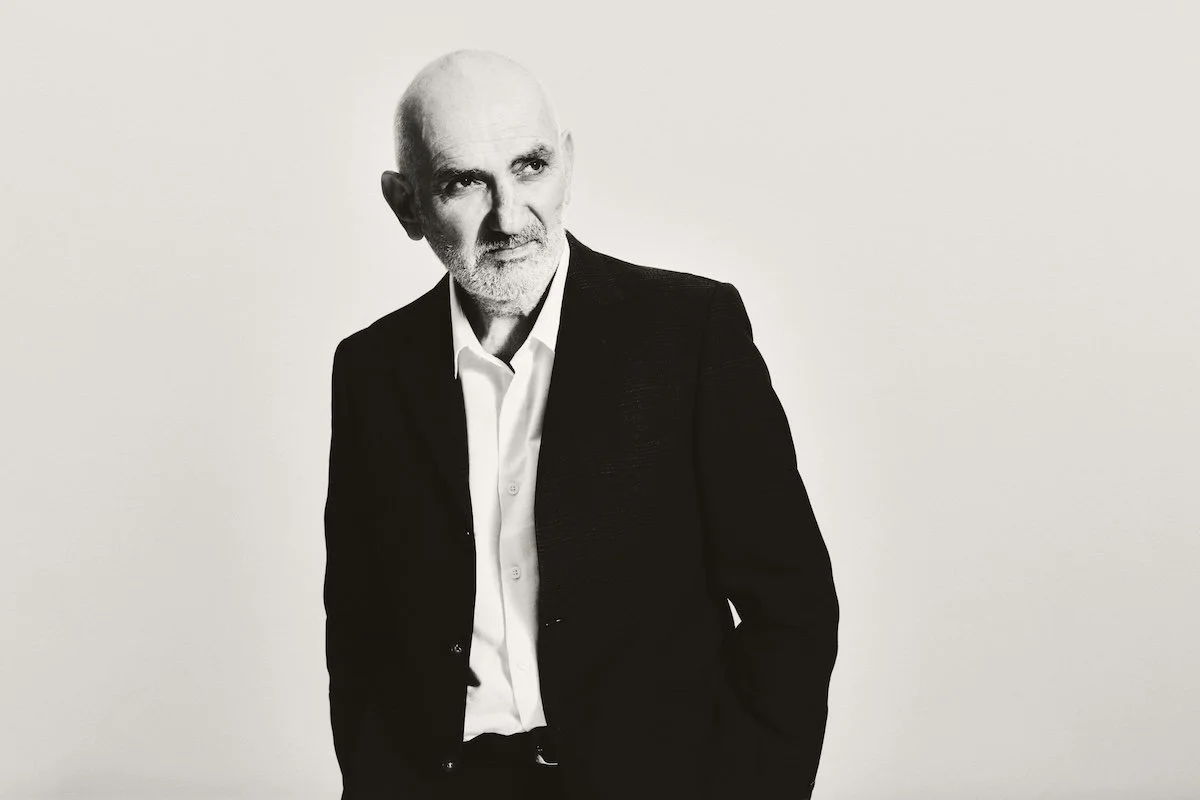

Paul Kelly: The Quiet Giant of Australian Songwriting

Joe Brennan

Born in a taxi in North Adelaide and raised on a diet of jazz, rock and pop records, Paul Kelly has spent half a century telling Australia's stories – not with noise, but with grace. We chat with the acclaimed artist about his early Influences, his relationship with Archie Roach and how he continues to challenge himself as a songwriter ahead of his national tour.

Over a career spanning more than 50 years, Paul Maurice Kelly AO has cemented himself as one of Australia’s greatest ever songwriters. Kelly has released 29 studio albums, three of which topped the charts, won an incredible 17 ARIA Awards and released some of the country’s most iconic songs, including ‘To Her Door’, ‘Before Too Long’, ‘Dumb Things’ and ‘How To Make Gravy’. As an artist, both solo and with groups the Dots, the Coloured Girls and the Messengers, Kelly has achieved a high level of success while managing to keep his true self under wraps.

Famously private, Kelly offers listeners a peek into his world through his songs without truly opening himself up. He is satisfied with audiences interpreting his music in their own way, weaving nuggets of his truth through the stories he tells that have resonated with generations of music lovers. Whether he does this knowingly is up for debate, but Kelly understands listeners will make the connection between the characters in his songs and his personal life. “I’m also aware that just by writing about the things you’re interested in, where the music and the words take you, you’re going to paint a portrait of yourself.”

This is no more evident than in Kelly’s iconic song ‘St Kilda to Kings Cross’. The track is an acoustic ballad about a man who moves from Melbourne to Sydney and mirrors Kelly’s life at that time, with the singer-songwriter having made the move to Sydney to escape the breakdown of his marriage and the end of his band. Then there’s ‘Leaps and Bounds’, a tribute to chilly autumn days at the MCG. Dig a little deeper and it’s clear that the song is Kelly recalling a childhood memory of heading to the footy and the excitement he felt. Rooted in Australian iconography, the song is a nostalgic tribute to his hometown of Melbourne. Kelly will never admit there are autobiographical elements in his music, but it’s hard not to see his life in his songs.

Born in the back of a taxi in North Adelaide to a lawyer father and a musically inclined mother, Kelly was raised in a warm environment where music featured heavily. As the sixth of nine children, the house was never quiet, with classical, jazz and rock records shaping Kelly’s musical influences. “In the early ‘60s, my older brothers and sisters were bringing records into the house,” Paul reminisces. “The first Beatles record and The Rolling Stones. Peter, Paul and Mary. A lot of the progressive rock stuff – Moody Blues, Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, bands like that.” Paul even remembers the first concert he went to – Yes, at Apollo Stadium. “It was amazing, it blew my mind.”

It was around this time that Kelly began to consider a career as a writer. Expressing himself through poetry, he fell in with a group of musicians who opened his ears to songs by ‘70s Americana artists such as Neil Young, Gram Parsons, The Allman Brothers and Joni Mitchell. Eventually, Kelly picked up the guitar and joined in. “I started playing guitar, and then one day, I just wrote a song. And then I thought, ‘Well if I can write one, I can write more’. So that sort of kicked it off, and it’s been one at a time ever since.”

Kelly’s songs have defined generations and offered hope to the hopeless. A master of words, he draws from the world around him for inspiration. A quiet, self-assured gent, he takes the craft of songwriting very seriously, although he admits to sometimes coming off “as quite vague or absent-minded”. To him, the key to songwriting is “keeping your ears open”. Listening to what people say, reading and immersing himself in other artists’ music influences his work. “Keeping yourself open [and] staying alert to what is around you is the main thing,” he explains.

For someone so prolific, Kelly’s take on the craft of songwriting is surprisingly stark. “Long periods of boredom, punctuated by the occasional surprise,” is how he puts it. He admits he doesn’t enjoy the process, but as mentioned, he stays open, always listening, reading, watching. “Songwriting is kind of fumbling around in the dark. So you’re always hoping, if I just stick with it, I’m going to get surprised at some point. You wait for the surprise.”

The first surprise came with the aforementioned ‘St Kilda to Kings Cross’, taken from Kelly’s 1984 record, Post. Although it failed to chart, he regards it as a “turning point” in his career. “That was the first time I felt I sort of found my own voice. I’d done a couple of records before then, which I didn’t like. [With] ‘St Kilda to Kings Cross’ – it felt like now I’ve sort of got my own patch of ground.”

Joe Brennan

The song got the attention of labels and landed Kelly a record deal with Mushroom, leading to the release of the acclaimed double album, Gossip. Joined by his band Coloured Girls (who would change their name to the Messengers), the album established Kelly as a major voice in the Australian music scene, blending radio-friendly melodies with his unmistakably Aussie lyrics. But just six years later, the band disbanded, with Kelly wanting to explore life as a solo artist.

He spent the rest of the ‘90s releasing a slew of folk-rock albums and collaborating with a host of Aussie artists, including the legendary Archie Roach, who had a great impact on his songwriting. “I met him in 1990,” Kelly recalls. “The story of his life and the hardships he went through and the way he dealt with it – the grace and compassion he had for everyone around him, the weight of the history that he bore and not just for him but for many of his countrymen. He was just a way to be in the world.”

Kelly has forged a close relationship with Indigenous Australians over the years, using his music to tell their stories without inserting himself into the picture. He comes at social issues at a human level, highlighting friendship, love and connection. While not overtly political, it’s clear to see which way he leans through his music.

One of Kelly’s biggest collaborations, ‘From Little Things Big Things Grow’, came about while camping with Indigenous musician, Kev Carmody. What originally started as a love song morphed into one of Australia’s most notable protest songs about Indigenous people’s struggle for land rights and reconciliation. “I generally write fiction,” Kelly states, “But I call these ones that are more based on true events or history, ‘Newspaper Songs’. I don’t have any big didactic sort of aims. I just think, for me, songs should point you somewhere.”

Kelly might “write fiction”, but it’s clear his music highlights his values and beliefs without forcing the issue. He uses his words to highlight stories and spark conversation, giving his audience the smallest morsel so they will hopefully explore further and learn more about what is going on in the world.

His career is littered with instances where he’s found himself in unique creative situations. Being willing and open led Kelly to collaborate with composer James Ledger, esteemed recorder Geneviève Lacey and members from the Australian National Academy of Music for the 2013 album, Conversations with Ghosts. “Sometimes, it’s good to say yes to things that seem pretty scary,” he says about the project. I said yes to it and then said, ‘Well, how am I going to do this?’”

Paul and James wrote 12 songs with lyrics derived from poems by Les Murray, W.B. Yeats, Judith Wright, Lord Alfred Tennyson and more. This was an unconventional method of songwriting for Kelly, who has always written melodies first and then added lyrics. “I never started with words first, as I thought that would be too restrictive. But it turns out I was completely wrong.” The result was one of Kelly’s most interesting pieces of work that led to him working with Ledger six years later on the classical album, Thirteen Ways To Look At Birds. The album won the 2019 ARIA Award for Best Classical Album and presented Kelly with another opportunity to explore his craft differently, something he’s been chasing his entire career. Yet even in these collaborations, his choice of story, tone, and restraint tells us something about the man behind the music.

“To find a new way of songwriting after 50 years felt like a great gift to me,” Kelly says, referencing Conversation with Ghosts. “All writers want to break their own habits. All writers want to find new ways to write – we all have our own grooves and channels, that rut we can get stuck in. So that opened up a whole possibility for me.”

Which brings us to the present and Kelly’s 29th studio album, Fever Longing Still. Universally praised, the 12-track album peaked at #3 on the ARIA Album Charts and reveals Kelly has lost none of his lustre as a songwriter, despite admitting he’s “writing less songs” than he used to. To celebrate the release, Kelly is hitting the road on his first arena tour, although it’s not without its challenges.

“We haven’t done an arena tour before,” Kelly muses, although he has performed to massive crowds alongside his heroes Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan, who he takes inspiration from for the tour. “They’re good models for the kind of show I want to do. They made the space feel intimate.” This is precisely what Kelly does: he invites his listeners into his world through song.

Anyone who has seen Kelly live can see the similarities between his heroes and his own stage persona. Kelly seems like he’s singing to each individual person in the audience, wrapping them up in his wonderful world that has given him the privilege of being on stage. It’s a unique experience for all those present and is a testament to Kelly as not only a performer, but a father, a son, a brother, a partner and a grandfather.

As proven throughout his career, Kelly has never been too concerned with preaching to his audience or fitting an agenda – he just wants to tell stories for as long as he can. “There’s some periods where I don’t think I’m ever going to be able to write another song,” he confesses. “That probably would’ve worried me in the past or made me anxious in some sort of way.”

But there’s always a story to tell – whether it’s being born in a taxi or tracing tangled histories across time and country. And while his songs have travelled far, they always find their way back to him.

Songwriting is how he makes sense of the world – and how he connects with it. “I think I write for me. But I’m a songwriter, I don’t have [songs] in my head, they need to be sort of pushed out through air for somebody to hear. I’m writing to be heard.”